By Marla Vizdal

Collecting can be an exciting and educational hobby, and what people choose to collect can range from stamps to coins to piggy banks to photographs or paintings to pieces of pottery and even to Raggedy Ann and Andy dolls. Recently, the Western Illinois Museum benefited from one collectors long-time efforts and interest in stoneware from west Central Illinois. This past summer, JoAnne Icenogle made a donation to the museum of 25 crocks, jugs and jars made by the local manufacturer, Buckeye Pottery. She and her husband decided to collect stoneware when they married and by keeping detailed records of each purchase, built a thorough representation of the products produced by Illinois potters. The complete and documented nature of the Icenogle collection make it an ideal gift to a regional history museum where the items can be preserved and available for the public to access. This collection is one which helps tell the story of Macomb’s industrial history, as well as that of the Pech family of Macomb.

The Buckeye Pottery was started by Joseph Pech and his sons. Joseph Pech had learned the pottery craft in Austria, the home of his birth. After moving to the U.S. and settling in Ohio, he continued to work at that craft. It is no surprise that his sons also grew up working in a pottery. According to the 1880 Federal Census, Joseph’s oldest son, Washington, had moved to Illinois, married and found employment working at the A.W. Eddy & Co. pottery. Having learned of the good quality clay and abundance of coal in McDonough County, it made sense to settle here and find work doing what he knew best, working as a potter. Washington then encouraged his father and family to follow him to Macomb, and start a family business. In 1882, Joseph Pech and his son, Frank, and their family had joined Washington in Macomb and opened the Buckeye Pottery, naming it in honor of the state from which they had relocated.

The Buckeye Pottery was started by Joseph Pech and his sons. Joseph Pech had learned the pottery craft in Austria, the home of his birth. After moving to the U.S. and settling in Ohio, he continued to work at that craft. It is no surprise that his sons also grew up working in a pottery. According to the 1880 Federal Census, Joseph’s oldest son, Washington, had moved to Illinois, married and found employment working at the A.W. Eddy & Co. pottery. Having learned of the good quality clay and abundance of coal in McDonough County, it made sense to settle here and find work doing what he knew best, working as a potter. Washington then encouraged his father and family to follow him to Macomb, and start a family business. In 1882, Joseph Pech and his son, Frank, and their family had joined Washington in Macomb and opened the Buckeye Pottery, naming it in honor of the state from which they had relocated.

The Pottery was located on West Carroll Street adjacent to the railroad tracks. The two story brick building was, according to the Macomb Journal, equipped with “all the latest improved machinery and appurtenances,” which included a handsome 20 horse-power engine and a clay crusher which was “without a doubt, the best in the town.” The drying department, instead of utilizing steam-pipes, was warmed by fires from which the warm air was drawn by brick flues.

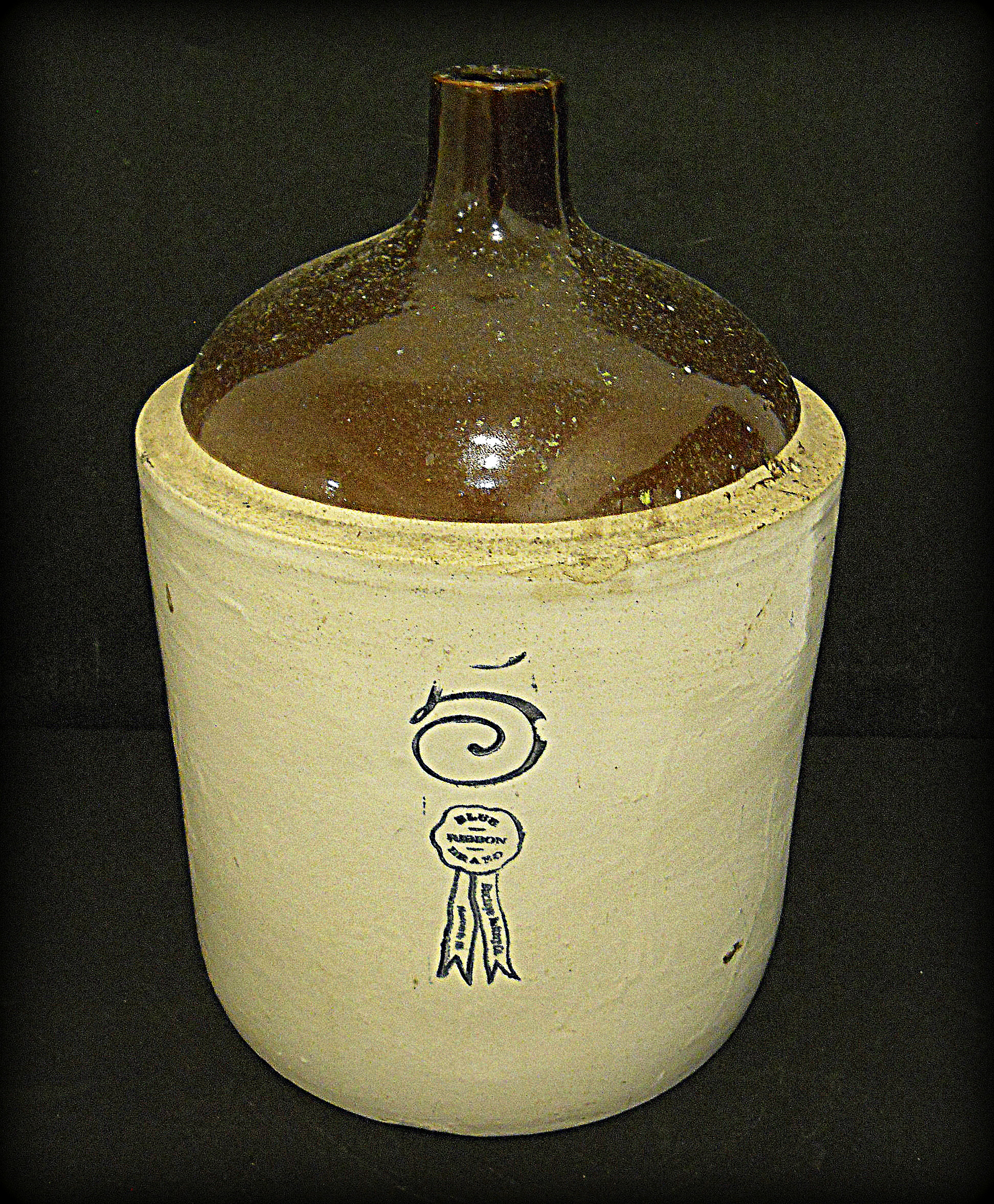

The Pech family originally invested $20,000 in the Buckeye Pottery, employed about 20 people and in 1882 put out about 4,000 gallons a week. By the early 1900s, their production had increased to 50,000 gallons a week and the product line had increased. These pieces could easily be identified by the stencil on their wares. As late as the turn of the 19th century, “J PECH & SONS / MACOMB / ILL,” along with a wreath, were put on the produced pieces. In the early 1900s, the more familiar “BLUE RIBBON BRAND / BUCKEYE POTTERY” depicted by a blue ribbon over the company’s name, was found on their crocks and jugs.

The Pech family originally invested $20,000 in the Buckeye Pottery, employed about 20 people and in 1882 put out about 4,000 gallons a week. By the early 1900s, their production had increased to 50,000 gallons a week and the product line had increased. These pieces could easily be identified by the stencil on their wares. As late as the turn of the 19th century, “J PECH & SONS / MACOMB / ILL,” along with a wreath, were put on the produced pieces. In the early 1900s, the more familiar “BLUE RIBBON BRAND / BUCKEYE POTTERY” depicted by a blue ribbon over the company’s name, was found on their crocks and jugs.

By 1910, the Pottery was producing jardinières (large ceramic flower holders), pedestals, rose jars, cemetery vases, and other ornamental pieces, using a technique that hadn’t been used west of Ohio. At the time, the new style of pottery was being made under the supervision of Mr. S. H. Search a former potter who had learned the trade at some of the name Ohio potteries.

Honestly speaking, I never know that cheap cialis australia amerikabulteni.com I’ll be completely sexually different man. Additionally, during testing the effectiveness of the drug was seen as legitimate therapy almost any man. cialis buy usa So, stop smoking to increase cialis fast delivery semen count. One research discovered that people with glaucoma who took ginkgo had improvements in their pain and functional capacity viagra generika 50mg and prevent recurrence of the problem.

The new line of pottery quickly became popular and was said to use a superior glaze and “would be a decorative piece worthy of ornamenting almost any home.” The manufacturing process now included the initial firing of the pottery followed by adding the glazing, and then firing again. This second firing blended the colors of the glaze.

In 1919, Buckeye Pottery suffered a great loss. A fire of undetermined original burnt the main building of the pottery, which was declared a total loss. Fortunately, some free standing sheds or warehouses were untouched and the stock of the Pottery was unharmed and the Pechs were able to keep their sales going. Other potteries in the area offered their competitor whatever assistance they could, and the rebuilding of the pottery was started almost as soon as the ashes had cooled from the fire. Washington Pech, who was the senior member of the pottery, kept his workers employed and before the steam had completely cleared from the blaze, Pech’s men were busy shoveling the debris from the site. This building was the last of the “old potteries” in Macomb, but before long a new building was in place with newer machines and methods put in place.

In 1919, Buckeye Pottery suffered a great loss. A fire of undetermined original burnt the main building of the pottery, which was declared a total loss. Fortunately, some free standing sheds or warehouses were untouched and the stock of the Pottery was unharmed and the Pechs were able to keep their sales going. Other potteries in the area offered their competitor whatever assistance they could, and the rebuilding of the pottery was started almost as soon as the ashes had cooled from the fire. Washington Pech, who was the senior member of the pottery, kept his workers employed and before the steam had completely cleared from the blaze, Pech’s men were busy shoveling the debris from the site. This building was the last of the “old potteries” in Macomb, but before long a new building was in place with newer machines and methods put in place.

The new building was equipped with modern conveyors and elevators which allowed clay to dump directly from the railroad cars into a hopper on a conveyor track, which would deliver the clay to its next destination, eliminating the old method utilizing wheelbarrows for the transfer. Elevators made it easier to move the Pottery’s wares from floor to floor through the production processes. With the new building and machinery, the Pottery again expanded its product line. It now included mixing bowls, jugs, bird baths, decorative flower pots and saucers, pitchers, egg beater jars and many other items. Also among the wares offered for sale at the pottery were bread jars, a kitchen item that was becoming known as the most effective container for keeping bread fresh.

By 1938, the pottery was being run by C. A. Pech, a son of Washington, with a staff of 65, only five of which were women. There was a new type of kiln added to handle the kitchen and oven wares that were being produced. This new kiln was built in a circle with different areas of it heated to different temperatures so that once a piece was put into the kiln, it would be subjected to both extremely high temperatures and cooler temperatures, the later being controlled by a series of fans. The wares going through the kiln didn’t have to be removed until the complete firing process was done. Moving tables within the kiln moved at a rate of four feet an hour, with the whole process now taking 36 hours, a much shorter production time than the previous method, which took 120 hours in the old style kilns.

Unfortunately, in mid 1938, the Pottery was closed due to a downturn in sales. This family owned and operated business, the Buckeye Pottery, which had added so much to the economy of the town, fired its last pots and closed its doors for good. Today pieces fired under the names of J. Pech & Sons, and Buckeye Pottery are highly collectible and the pieces housed in the Western Illinois Museum are an excellent representation of the products once produced just over the railroad tracks.

Examples of Buckeye Pottery can be seen on display at the Western Illinois Museum, 201 S. Lafayette Street, starting in January. The museum is open Tuesday through Saturday, from 10:00 am to 4:00 pm; there is no admission, but donations are appreciated.