By Logan Elko

Intern, Western Illinois Museum

The featured artifact from the collection of the Western Illinois Museum is a Civil War-era sword. This sword was carried by Captain William Ervin of the 84th Illinois Infantry. Captain Ervin spent his adult life in Macomb, and was a person of good standing within the community.

The sword was made by Rohrig and Company in Solingen, Germany. The sword is ornate in its design, with a floral pattern typical of European sword designs of the era. The sword also features the acronym “US,” both on the sword and on the guard. This sword is most alike the Model 1850 Staff and Field Officer’s sword that was standard for officers during the Civil War. Swords, however, were not issued by the government. Officers were responsible for purchasing their swords, and there were no regulations limiting swords to officers.

Captain William Ervin was born in Rockingham County, Virginia, in 1820. In 1841, William moved with his mother to McDonough County to live with his older brother, Hugh, who had moved to Macomb. From 1841 until 1862, William ran a mercantile business with his brother Hugh on the Macomb Square. During this time, he was married to Mary McCrosky, with whom he had three children.

According to the Macomb Journal, William Ervin was unable to enlist due to an illness in 1861, but his brother Hugh served in the 28th Illinois Infantry and served as its quartermaster until he resigned on January 31, 1862. Unlike today, during the Civil War officers could resign their commission and return home during the war. Some did this so that they could return to their home state and raise a new regiment, but others, like Hugh, resigned for other reasons.

On June 9, 1862, William Ervin enlisted in C Company of the 84th Illinois Infantry as a captain and would be responsible for raising C Company in Macomb. Captain Ervin’s age at enlistment was older than the average, as he was around forty-two at the time. Ervin continued recruitment in Macomb alongside the sheriff, S.J. Hopper until August, until the regiment rendezvoused in Quincy, a term used to describe the gathering of men to being drills. From June 1862 until June 1865, Ervin would participate in all the engagements in which his company took part. Upon leaving the army, Ervin was brevetted to the rank of major but would remain known as “Captain” throughout Macomb for the rest of his life.

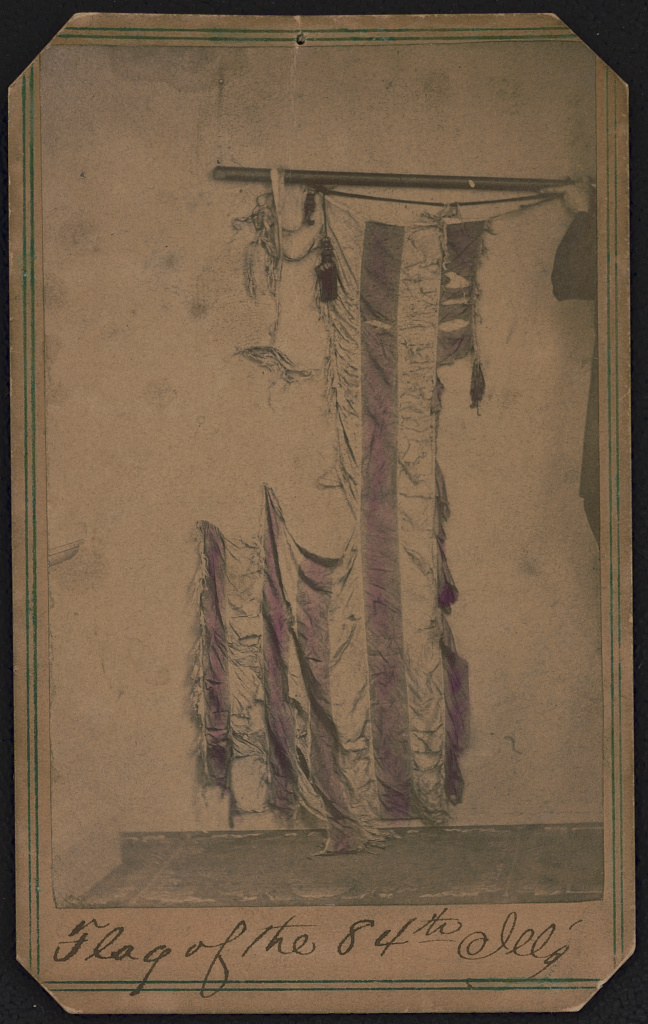

The 84th Illinois Infantry fought in the Western Theater during the Civil War, and participated in the Battles of Stone River, Chickamauga, Lookout Mountain, and others. It was a volunteer regiment, raised by Louis H. Waters, of Macomb. Colonel Waters began to train the regiment during August in Quincy, Illinois. Training, this early in the Civil War, consisted of nothing more than learning how to march and learning how to form ranks. The army did, however, provide manuals for its officers to read and learn tactics. These tactics manuals were heavily influenced by Napoleonic Era tactics, which were the common military strategies employed at the time. Captain Ervin, although not formally trained, had access to these manuals, but probably would have relied more so on his influence over his men to command effectively.

The regiment was mustered into the army on September 1, 1862, at Quincy, Illinois. According to the regimental history, the regiment was equipped with English-made Enfield muskets, which were rifled, and according to Louis A. Simmons, the author of the history, were “eventually decided the best for the infantry of any in use.” Aside from the weapons, not much else was issued to the men.

On September 23, the regiment received its marching orders to report to Louisville, Kentucky. Upon arrival, the 84th was assigned to the Tenth Brigade of the Fourth Division and was marched with the Army of the Ohio to pursue Confederate general, Braxton Bragg. While in Louisville, the regiment was subjected to a constant threat of attack that never materialized. The men were said to have stood in the streets of Louisville for the entirety of the night, waiting for an attack that never came. This first “encounter” with Confederate troops foreshadowed the experiences of the 84th. It was soon discovered that the Confederates had broken camp and had begun to retreat towards Nashville, and so the 84th marched as a part of the Army of the Ohio to purse the Confederate army. The regiment did not remain a part of the Army of the Ohio for long, as they were transferred to the Army of the Cumberland shortly before the battle of Stones River.

General Rosecrans assumed command of the Army of the Cumberland in Nashville, Tennessee. The men welcomed the change of command and soon were thrust into their first major engagement of the war, the Battle of Stones River. The regiment lost 228 men during their first engagement with the enemy. During this first engagement, the 84th was a green company and completely new to combat. Captain Ervin commanded C Company of the 84th and during the battle would have relied not on his skills as a tactician, but on his relationship with his men to maintain control and direct their actions. Captain Ervin, during Stones River and all subsequent battles, would not have had the authority to move his company independently of the rest of the regiment, but instead would have listened for commands from other soldiers who used drums or bugles to rally the companies.

The next major engagement that the 84th participated in was the Battle of Chickamauga. At Chickamauga, the 84th was subjected to constant fire from the Confederates and during the battle, the 84th manned fortified positions to help defend against the Confederate attack. The 84th was subjected to the Confederate charges that ultimately caused the defeat. The regiment was a part of Colonel Beatty’s brigade and was routed from the field on the third day of the battle. The battle proved to be a victory for the Confederacy, as the Union army was forced to withdraw to Chattanooga. The 84th suffered 172 casualties during the battle.

As a result of the withdrawal, the Confederate army captured Lookout Mountain, the site of the 84th’s third major engagement. The 84th during the Battle of Lookout Mountain did not take part in the charge up the side of the mountain but instead fought across the shallow creek on the left flank of the main assault. The 84th, when attempting to cross this creek became encumbered by the picket lines of the Confederates on the opposite side. The 84th did eventually cross the creek, along with the rest of the army capturing the summit of Lookout Mountain. With this Union victory, Bragg never was again able to contest the city of Chattanooga.

After the Battle of Lookout Mountain, the 84th marched with General Sherman to Atlanta and took part in the siege. After the battle, the 84th was placed under the command of Major General Taylor, then known as the Rock of Chickamauga, and was sent to defend Nashville, Tennessee. This was the last assignment the 84th took part in, and thus Captain Ervin’s last assignment as well. By then it was 1865 and the regiment was close to fulfilling its three-year contract. The war ended with Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Courthouse, but the 84th was not mustered out of the Union Army until June 8, 1865, at Camp Harker in Tennessee.

Before its first encounter with Confederate troops, the regiment numbered 951 men, but by the end of the war, the regiment had suffered 558 casualties in battle. The 84th fought valiantly at the Battle of Stones River, the Battle of Chickamauga and the Battle of Lookout Mountain.

The 84th Illinois had annual reunions after the war starting in 1882. At these reunions, the veterans and their families would gather at different towns and remember their experiences. The meeting at Vermont in 1893, after Captain Ervin’s death, was featured in the Macomb Journal, and the article describes some of the happenings. The regiment gathered at a Grand Army of the Republic, a veteran’s group for Union soldiers, (G.A.R.) hall and from there marched to the Christian Church. At the Christian Church, the regiment was provided dinner, business was held, and entertainment was provided. At these meetings the regiment would vote on the next year’s location. Prior to his death, Captain Ervin attended the regiment’s reunions.

Upon returning to Macomb, Ervin was honored by the Macomb Journal for his service during the war. He would also be known as “Captain Ervin” for the rest of his life in McDonough County. Later the same year, 1865, the Captain was elected to serve as the county clerk for McDonough County. Aside from his duties as a county clerk, Captain Ervin was active in the Republican Party, and he attended the 1868 Republican National Convention, alongside Colonel Waters and C.V. Chandler.

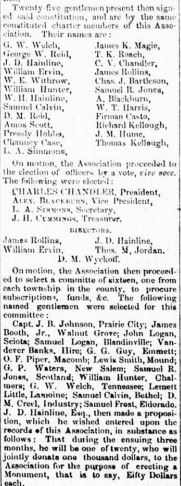

William Ervin was also a member and director of the McDonough County Soldier’s Monument Association. Some notable members of the association were: C.V. Chandler, Louis A. Simmons, Alex Blackburn, and J.H. Cummings. The association was formed to procure the funding to erect a monument in the Macomb Public Square. It is probably through this group that the monument in Chandler Park was erected.

After his term as the county clerk, the Captain attempted to farm. He owned a farm in Scotland Township, but he had little success. Ervin gave up farming and sold his property in 1872.

In 1871, Captain Ervin opened his successful drug store and ran the business with his son, James M. Ervin. The family store advertised in the Macomb Journal and ran ads for their products. The Captain died in 1891 of old age, and he was at Oakwood Cemetery in Macomb. His widow, Mary, received his pension of eight dollars a month and an initial payment of $190 in back pay. Captain Ervin’s command experience and his combat experience during the Civil War influenced his life after the Civil War.